MEN IN BLACK FORETELLS 9/11

or, "People Are Smart — J/K"

For better or worse, I’m a millennial, which means I wasn’t yet born when Venkman, Stantz, and Spengler were busting ghosts and cracking wise all over the movies, TV, and lunchboxes. For me Ghostbusters was just another monolithic VHS tape on the walls of Dave’s Video, and for a long time I thought I had missed out on that particular pop-culture phenomenon, but it occurs to me now that, while I wasn’t around for all that, I got basically the same experience in 1997 with Men in Black. Keep the New York setting, but change the overalls to black suits and the wacky paranormal ghosts to zany extraterrestrial aliens—somehow find the perfect young-upstart meets cranky old-timer chemistry in Will Smith and Tommy Lee Jones—and voila: another summer blockbuster appears.

Men in Black worked well for many reasons. The tone it struck (basically Ghostbusters meets The Blues Brothers) was aimed at two distinct audiences, kids and adults. The kids (that was me, Alex) could go see it and laugh at the aliens and effects and Will Smith saying “aw dayum,” while the adults (my dad, who didn’t enjoy movies, generally, or maybe just not the movies my Mom and I wanted to see) can go see it and laugh at all the grown-up jokes, most of them uttered by Jones or Rip Torn—and then those kids can grow up and watch again to finally understand what old dad was laughing about—and the loop repeats. I only dimly remember the theatrical experience, but I spent the subsequent years watching the tape over and over.

My experience up to this point is likely not unique. This movie was an enormous hit. It launched Will Smith to superstardom, and stamped itself on my generation as one of a handful of hugely popular media in the 1990s that primed our later taste for the supernatural. And yet at the time we were all watching with eyes wide shut. When Alice tells her husband in the opening moments of Kubrick’s final puzzle piece, “you’re not even looking,” this was Kubrick talking to us, the audience—not just of his films, but of cinema (and perhaps reality) as a whole. In 1997 we were simply not looking at what was being put in front of us. We thought it was entertainment.

It’s only now almost 30 years later that we are beginning to find the context needed to see that Men in Black was actually more like entrainment — 100% unequivocally a pre-game ritual for the events of 9/11/2001.

I can prove it, but before I do, a little context on how I got here. I didn’t just wake up one day and realize this. Nor did I even happen upon it by sheer chance or accident while watching the film again one day. And I certainly didn’t get it from some video on TikTok. The fact is I was directed to this information about a year ago – specifically I was directed to it by the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Gordon Cole, practically yelling into my ear. Yes, it was David Lynch who put me onto this.

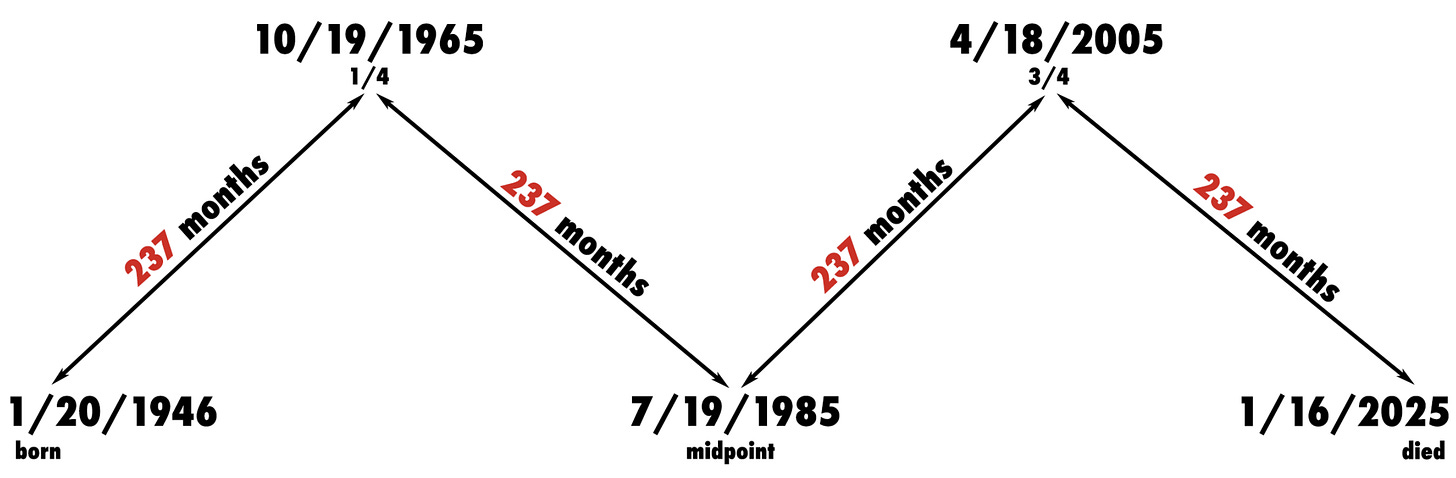

How did he do this you ask? By dying. When David Lynch died on 1/16/2025 I did the same thing I do when anyone expires: measure the lifespan, find the mid-point. I was amazed to discover that, having passed away only 4 days before his 79th birthday, Lynch had lived for 4 blocks of 237 months (99.9% exact). Naturally I went ahead and divided his life into quarters to examine each node for synchronistic residue, and guess what dividing a life into quarters creates?

It’s cosmic! It’s cosmic! A full explication of this marvelous Lynch-span structure will be published here in the future. Here we only need to traverse the first “peak” to understand what led me to Men in Black. One search for 10/19/1965 turned up the fact that this is the canon birthday of Agent J, the character played by Will Smith in all three films.

So the fictional “Agent J” was born when the actual David Lynch was 237 months old. It got me thinking. Lynch essentially made his own take on the Men in Black when he made Twin Peaks. Agent Cooper (Agent C?) famously sports the “black suit, black tie,” as do Gordon Cole and Albert Rosenfield. The show is about a group of well-dressed occult cops chasing down “alien funny business,” just like Men in Black.

That was enough for me. It was time to put away the nostalgia, and take a serious look at Men in Black through the Crypto-K electron-microscope, specifically mining it for resonance with Twin Peaks and Lynch, and of course Stanley Kubrick. What I found was a shockingly precise internal architecture. It’s not just in the images or sound; 9/11 is edited into the very geographic and temporal fabric of the film. Either the writer, director, editor, production designer, cinematographer, etc. were all in on this together, or they were all being puppeteered by an otherworldly force (PKD called it Ubik; Crypto-K calls it Kubrick). There is no in-between.

“Today we’re going to concentrate on the J’s.” – Agent Cooper

In Men in Black, Will Smith plays a spirited New York cop named James Edwards who is recruited into the world’s secret alien police-force by the older Agent K (played by Tommy Lee Jones) after coming to their attention by running down and cornering an alien on foot. Before striking a Christ pose and falling backwards off a roof to his death, the alien reveals himself to James when he appears to “blink with two sets of eyelids.” After reading the report, the Police chief asks James, “You mean he blinked with both eyes?” “No, sir, he blinked one set, then blinked an entirely different set.”

Just for the record, couldn’t we call those, twin peeks?

The Men in Black film franchise officially derives from a 1990-1991 comic book, itself based on the real-life lore about strange men clad in black suits appearing out of nowhere to intimidate UFO witnesses into silence. Stories of this ilk have been circulating for about as long as UFO encounters have been a thing, but for some reason in the 1990s the archetype pushed its way to the forefront of the collective consciousness. Except in the 1960s and before they were generally seen as devils, villains—seemingly non-human in origin—but by the 1990s, the MIBs had become the good guys (“Jose Chungs From Outer Space” notwithstanding).

Remember that the Men in Black comic book wasn’t the only story released in 1990-1991 that involved a secretive department of paranormal agents wearing black: that was the same year as the original run of Twin Peaks. The 1997 film traded Agent Cooper’s trench-coat and tape recorder for hip sunglasses (lifted from The Blues Brothers, also based on the MIB lore) and the phallic red-eyed Neuralyzer, but the basic idea remained: occult cops dealing with alien funny business and looking low-key fire while doing so.